Taiwan`s libel law clashes with UN rights standards

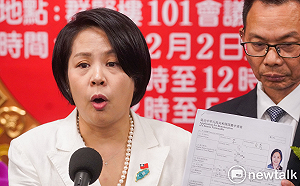

The charges of criminal defamation filed by ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Legislator Hsieh Kuo-liang (謝國樑) against New Talk publisher Su Jeng-ping (蘇正平) and New Talk reporter and Association for Taiwan Journalists President Lin Chao-yi (林朝億) have reignited concern over whether Taiwan`s retention of criminal defamation infringes on our constitutional rights of freedom of expression and news freedom.

Hsieh filed the charges under Article 310 of Taiwan`s criminal code and also filed a suit with the Taipei District Court to seize the assets of the two journalists in the wake of an article published in New Talk on September 2 that reported on meetings with Hsieh and members of the National Communications Commission before NCC hearings on the controversial application of the Want Want China Broadband to purchase 11 cable television companies for NT$76 billion.

The ins and outs of the two suits and the implications of the Want Want case have been discussed in depth elsewhere, but Taiwan citizens and news media workers should pay close attention to the question of the use of criminal defamation charges by politicians and other public personages in reaction to negative media coverage and the implications for Taiwan`s overall level of news freedom and freedom of expression.

In the wake of the controversy, global human rights and news freedom organizations including Freedom House and the International Federation of Journalists have expressed concern over the case and issued calls for the decriminalization of libel in Taiwan.

Citizens and news workers might have anticipated that the question of decriminalization of libel might have been raised in the wake of the incorporation into our domestic law of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights effective December 10, 2009.

However, Article 310 and the question of whether defamation should be decriminalized have not been included in the review of Taiwan`s legal code and administrative regulations now being conducted under the auspices of the Presidential Advisory Commission on Human Rights chaired by Vice President Vincent Siew.

Part of the reason for this omission may be the fact that Taiwan`s Constitutional Court found in its Interpretation No. 507 of July 7, 2000 that Article 310 does not violate the constitutional right of freedom of speech in Article 11 on the grounds that the criminalization of defamation is ``a necessary countermeasure`` to ``protect individual legal interests`` and ``to prevent the infringement of the freedom and rights of other persons.``

The Constitution Court determined that ``if the law allowed anyone to avoid penalty for defamation by offering monetary compensation, it would be tantamount to issuing them a license to defame.``

New UN interpretation

However, the validity and weight of this interpretation and the apparent official belief that criminal defamation does not violate the two covenants has now been called into question by the issuance on July 29, 2011 of ``General Comment No. 34`` by the Human Rights Committee, the United Nations agency responsible for interpreting the ICCPR, on ``Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression.`` (http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/comments.htm)

The HRC`s General Comments or interpretations of the ICCPR are considered to be binding for all signatory ``state parties.`` Even though Taiwan is not a UN member and has not been able to deposit its ratification with the UN Secretariat, the global human rights community and Taiwan law itself considers these General Comments as binding in effect.

Indeed, Article 3 of the implementation law for the two covenants (兩公約施行法) requires that ``applications of the two covenants should make reference to the legislative purpose and the General Comments of the Human Rights Committee.``

Naturally, the current review of the Taiwan legal code to find and revise features not in accord with the two covenants is one such ``application`` that must ``make reference to the legislative purpose`` of the ICCPR and ``the General Comments of the Human Rights Committee.``

The product of years of discussion among ICCPR signatory states, General Comment No 34 is the first ICCPR interpretation released by the Human Rights Committee since Taiwan ratified the two covenants and is directly relevant to the re-examination project and the current defamation case against the New Talk journalists.

Specifically, Article 47 mandates that ``defamation laws must be crafted with care to ensure...that they do not serve, in practice, to stifle freedom of expression.``

Moreover, the HRC`s interpretation mandates that ``states parties should consider the decriminalization of defamation and, in any case, the application of the criminal law should only be countenanced in the most serious of cases and imprisonment is never an appropriate penalty.``

In addition, Article 47 stated that ``at least with regard to comments about public figures, consideration should be given to avoiding penalizing or otherwise rendering unlawful untrue statements that have been published in error but without malice`` and that ``a public interest in the subject matter of the criticism should be recognized as a defence`` and adds that ``care should be taken by States parties to avoid excessively punitive measures and penalties.``

All of these stipulations are relevant to the current case, which evidently concerns a matter in which there is well-justified ``public interest`` in preventing the monopolization of Taiwan`s news media, in which a criminal defamation suit has been filed by a ruling party legislator with the apparent intent of ``stifling freedom of expression`` and in which the legislator in question is utilizing the mechanism of the (already proceeding) seizing of the assets of the two journalists as an ``excessively punitive measure.``

Moreover, the HRC`s General Comment declares in Article 2 that ``freedom of opinion and freedom of expression are indispensable conditions for the full development of the person and ... constitute the foundation of every free and democratic society.``

In Article 3, the HRC posits that freedom of expression is a necessary condition for the realization of the principles of transparency and accountability that are, in turn, essential for the promotion and protection of human rights.``

Therefore, the HRC finds in Article 5 that freedom of opinion and freedom of expression ``cannot be made subject to derogation,`` or even partial revocation or discounting even in a state of emergency, and mandates in Article 6 that ``the obligation to respect freedoms of opinion and expression is binding on every State party as a whole,`` including the executive, judicial and legislative branches of government at any and all levels.

Such an interpretation, to put the matter mildly, clearly calls into question the validity of the Constitutional Court`s July 2000 finding that criminal defamation and possible imprisonment for expression or news reports does not conflict with the right of free speech.

The new General Comment contains other significant provisions on freedom of expression and the media, the right of access to information, the relationship of these freedoms to political rights and the limited allowed scope on restrictions of freedom of expression in certain areas, including the question of libel and measures to prevent official or private sector media monopolies.

In any case, the declaration by the UN`s Human Rights Committee that signatories of the two covenants ``should consider the decriminalization of defamation`` sends a signal that Taiwan`s continued retention of criminal defamation is decidedly ``not in accord`` with the two covenants, international human rights standards and, since the law adopting these two covenants into our domestic law, Taiwan`s own legal code.

The Ministry of Justice and the presidential advisory commission on human rights should take the initiative to add repeal of Article 310 of the Criminal Code and other related articles and measures to its worklist for of rules that must be revised before the expiration on December 10, 2011 of the two year deadline set by the implementing law for the two covenants for such revisions.

In addition, the Taiwan government ``should consider`` following the advice offered October 26, 2011 by the International Federation of Journalists and ``institute defamation as a civil defence with relevant safeguards for press freedom and the ability of journalists to report on matters of public interest.``

Given the requirement of Article 6, the current KMT administration of President Ma Ying-jeou, the KMT-controlled Legislative Yuan and the Judicial Yuan should also re-examine their own actions and policies to bring them into accord with the ICCPR and General Comment No. 34 and reverse the evident decline in Taiwan`s news freedom since Ma took office in May 2008.

by Dennis Engbarth

中文全文如下:

儘管馬政府信誓旦旦要與國際接軌,簽署《公民與政治權利國際公約》與《經濟社會與文化權利國際公約》兩公約時大聲嚷嚷說是要保障人權,但現行刑法規範的毀謗罪卻抵觸聯合國規章,引起訾議。

國民黨立委謝國樑以刑法的毀謗罪對付記者林朝億,以及網路媒體新頭殼的負責人蘇正平,令人憂心臺灣保留刑法的誹謗罪侵犯了憲法所保障的表意自由與新聞自由。

謝國樑引用刑法第310條對兩人提起告訴,並訴請台北地方法院假扣押兩位記者的財產,理由是9月2日的1則報導揭露了謝某在國家通訊傳播委員會(NCC) 針對旺中寬頻併購案進行聽證前夕,約見該會的官員。旺中寬頻準備以新台幣760億元的代價,併購臺灣11家有線電視公司,引發各界爭議。

台灣的公民與新聞媒體工作者應該特別留意政客和其他公眾人物在面對負面報導時採取刑事毀謗官司作為手段的問題,以及這種現象對臺灣整體新聞自由和表意自由意味著什麼。

本案爆發後,全球人權組織與新聞自由組織,如自由之家與國際記者聯盟均已表達關切,並呼籲臺灣解除以刑法來對誹謗相繩的作法。

台灣的公民和新聞工作者曾經以為當局在2009年12月10日簽署兩公約時,可以檢討誹謗除罪化的問題。然而,副總統蕭萬長所主持的總統府人權諮詢委員會在檢討法典和行政法規法時,卻沒有將刑法第310條以及誹謗除罪化的問題列入審查。

當局之所以會略過誹謗罪的問題,可能是因為大法官會議在2000年7月7日所做成的第509號釋憲案,裁定刑法第310條沒有觸犯憲法第11條所保障的言論自由,理由是以誹謗入罪是「誹謗罪即係保護個人法益而設」、「為防止妨礙他人之自由權利所必要」。

大法官會議在該號解釋文的理由書上寫道:「一旦妨害他人名譽均得以金錢賠償而了卻責任,豈非享有財富者即得任意誹謗他人名譽,自非憲法保障人民權利之本意。」

然而,這號大法官解釋的效力與份量,以及當局認定刑事誹謗罪沒有觸犯兩公約的信念,最近卻受到更具權威性的機關挑戰。人權事務委員會是聯合國內部負責詮釋 《公民與政治權利國際公約》的主管單位,2011年7月29日發佈了「第34號總合性解釋文」(General Comment No. 34)後,解釋該公約第19條「意見與表達自由」。(http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc /comments.htm)

人權事務委員會的「一般意見」以及該會對《公民與政治權利國際公約》所做出的詮釋,對所有的簽約國全部都有約束力。儘管台灣不是聯合國的會員國,也無法將其批准文送呈聯合國秘書處,全球的人權社群和台灣的法律本身都承認「總合性解釋文」拘束力。

的確,《兩公約施行法》第3條就規定「適用兩公約規定,應參照其立法意旨及兩公約人權事務委員會之解釋。」

很自然的,當前台灣的法典和法律見解與兩公約相抵觸之處,就「應參照」兩公約的「立法意指」以及「人權事務委員會之解釋」。

「第34號一般意見」是《公民與政治權利國際公約》簽約國經過多年討論的產物,也是人權事務委員會在台灣批准本公約後,針對本公約所發佈的第一道解釋。這號「一般意見」也就直接與當前謝國樑針對新頭殼記者所提出的刑事誹謗官司有關。

具體來說,這號「一般意見」對第47條的解釋,規定「毀謗法必須謹慎地處理,以確保…不被用來扼殺表意自由。」

再者,人權事務委員會的解釋命令「各國應考慮解除使用刑法對誹謗相繩,並且在任何案件中,應該只有在最嚴重的案件時才可以適用刑法,而監禁絕對不是一個恰當的懲罰。」

這條解釋還規定,「至少在處理有關公眾人物的相關評論時,應該避免懲罰對有錯誤但沒有真實惡意的報導加以懲罰,或以違法相繩」,並且「當被批判的事務本身 事屬公共利益時,這樣的言論應當被成認為一種(正當的)防衛」。該條文還要求「各國應當特別注意,避免採取懲罰措施和懲處。」

以上這些解釋全部都與謝國樑提出的誹謗官司有關。本案確實是牽涉到「公共利益」,目的是為了防範台灣的新聞媒體被壟斷,而提出誹謗訴訟的國民黨立委有明顯的意圖要「扼殺表意自由」,他利用了假扣押的機制作為「懲罰措施」。

再者,人權事務委員會的這號「一般意見」對第2條的解釋說,「意見自由核表意自由是人格發展所不可或缺的先決條件…也構成了每一個自由和民主社會的根基。」

在第3條中,人權事務委員會聲明,表意自由式落實透明化與問責性原則的必要條件,而透明化與問責性都是推動並保障人權所必不可少的。

因此,人權事務委員會在第5條中說,意見自由和表意自由「不可以被毀損」,甚至在國家危難的狀態下也不能打折扣。第6條則說,尊重意見自由與表意自由的義務,對每一個國家的行政、司法與立法部門和各層級政府全部都有拘束力。

就算用最溫和的說法,這號「一般意見」也明白地使台灣大法官會議在2000年7月所做出的「刑法毀謗罪合憲」之解釋文效力被打上1個大問號。

無論如何,聯合國人權事務委員會要求各簽約國「應該考慮誹謗除罪化」釋放出來的信號是,台灣這種死守刑事誹謗罪的作法是明顯抵觸兩公約、國際人權標準,以及台灣自己的《兩公約施行法》。

台灣的法務部和總統府人權諮詢委員會應當在2011年12月10日實施兩公約滿兩年之前,採取行動修改刑法第310條和其他相關法規。

此外,台灣政府還「應該考慮」採取國際記者聯盟在2011年10月26日所提出的建議,「將誹謗改為民事攻防,以保障媒體自由與記者報導公共利益事項的能力。」

掌握政權的馬英九總統以及由國民黨所主導的立法院和司法院,應該根據第6條的規定,重新審視自己的行為和政策,以符合《公民與政治權利國際公約》和「第34號一般意見」,並使自馬英九於2008年上台後明顯惡化的台灣新聞自由得以改善。

(文章僅代表作者觀點,不代表Newtalk新聞立場。)